Every country has a story of victory or freedom to tell, and Nigeria is not an exception. Many Nigerians are familiar with the reason why we celebrate Independence Day on October 1st of every year, but are not familiar with the stories behind the scenes.

Although, Nigerians still ask questions on whether or not they are independent or if they are indeed free. This is a result of some pressing issues or problems cutting across the economic, social and political sectors- especially as it relates to the constant thirst for foreign aid, corruption, migration, and foreign businesses, among others.

Some Nigerian scholars and researchers are of the opinion that Nigeria still directly or indirectly rely on those who colonized them. They believe that Nigeria was growing at its own pace in all sectors, until the advent of imperialism. Some scholars because these proposed theories (dependency and modernization theories) to examine Nigeria’s colonization by the Europeans. To them, independence is just a remembrance that the Europeans left the country, but are literally still ruling them.

In this piece, Naijabiography narrates the story that preceded independence and the history of how Nigeria gained independence.

History

The Southern Nigeria Protectorate and the Northern Nigeria Protectorate were united in 1914 to form the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria, which encompasses modern-day Nigeria. The country was granted independence on October 1, 1960, as the Federation of Nigeria, following the push for independence of African territories and the demise of the British Empire in the late 1950s. The constitution was changed three years later, and the country was renamed the Federal Republic of Nigeria, with former Governor-General Nnamdi Azikiwe as the first President.

Since the second millennium BC, Nigeria has been home to various indigenous pre-colonial nations and kingdoms, with the Nok civilization in the 15th century BC being the country’s first internal union. The contemporary state arose from British colonialization in the nineteenth century, and Lord Lugard’s merger of the Southern and Northern Nigeria Protectorates in 1914 gave it its current territorial configuration. In the Nigerian region, the British established administrative and legal institutions while exercising indirect rule through traditional chiefdoms.

Nigeria went through a civil war from 1967 to 1970, then a series of democratically elected civilian governments and military dictatorships until establishing a stable democracy in the presidential election of 1999; the 2015 election was the first time an incumbent president lost re-election.

Nigeria During the Pre-Colonial Era

There were no defined countries in West Africa throughout the 12th century; instead, there were several empires, kingdoms, and states of various kinds. Archaeologists believe one of the first complex societies in Western Africa formed in the southern section of today’s Nigeria, further west. This location, known as Igbo-Ukwu, was thought to have existed since 900 CE but was not as developed. By the 12th century, the region had established well-organized trade networks with other African ‘states.’

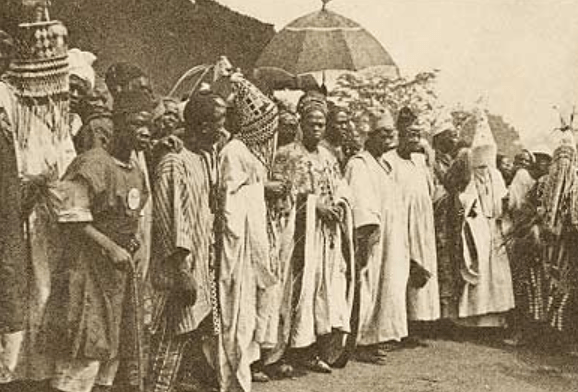

Trade was one of the most significant areas of life at the time. There are a few distinct groups in Nigeria, including the Songhay Empire, the Yoruba Empire, and the Kaneem-Borno, with a small bit of the Mali Empire thrown in for good measure. The Yoruba Empire, which is located in modern-day Nigeria and which I will highlight, was the most important Nigerian empire. There are three states/kingdoms within the Yoruba Empire: the State of Ife, the Kingdom of Benin; and the Kingdom of Oyo.

During the 15th century, Oyo and Benin overtook Ife as political and economic powers, but Ife retained its religious significance. Respect for the Ooni of Ife’s priestly functions was a key aspect of Yoruba culture’s development. Oyo adopted the Ife model of government, with a member of the royal family controlling multiple lesser city-states. The Alaafin (king) was named by a state council (the Oyo Mesi), which operated as a check on his power. Their capital city was located around 100 kilometres north of modern-day Oyo.

Unlike the forest-bound Yoruba kingdoms, Oyo was located in the savanna and relied on its cavalry forces to achieve hegemony over the neighbouring Nupe and Borgu kingdoms, paving the way for trade routes to the north.

The Benin Empire (1440–1897; locally known as Bini) was a pre-colonial African state located in what is now Nigeria. It is not to be confused with the modern-day country of Benin, which was originally known as Dahomey.

Finally, the Kingdom of Oyo, which began as a notable city in modern-day Nigeria and grew into a great empire, was founded in the southwestern section of the country. They eclipsed the State of Ife in terms of authority in the 15th century, but Ife remained a flourishing religious centre. The Kingdom of Oyo was at its peak in the 17th and 18th centuries. This is when the Kingdom of Oyo conquered the Dahomey Kingdom, which was located in modern-day Benin, and stretched its territory to the southern Atlantic coast. The Kingdom of Oyo, like the State of Ife, ensured that their kingdom was located on a major commercial route, making the construction of a large kingdom relatively simple.

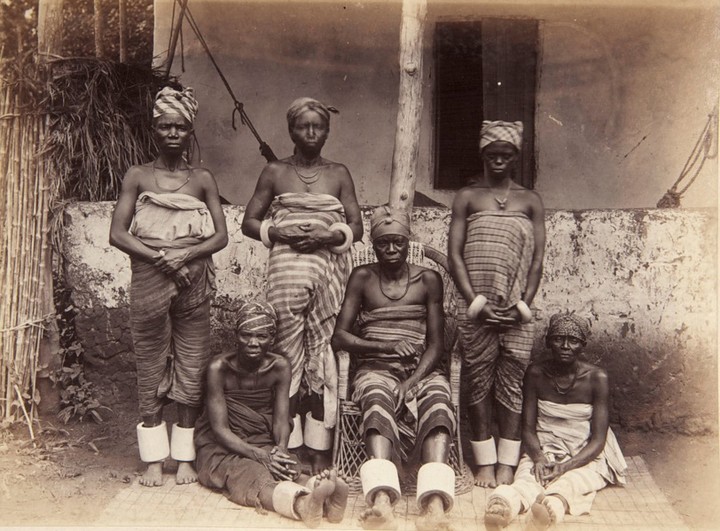

Portuguese explorers were the first Europeans to establish significant direct trade with the peoples of southern Nigeria in the 16th century, at the ports of Lagos, which used to be Eko and Calabar along the region’s Slave Coast. Europeans traded commodities with natives living along the shore, which also marked the start of the Atlantic slave trade. During the transatlantic slave trade, the port of Calabar on the historical Bight of Biafra—now known as the Bight of Bonny—became one of the greatest slave-trading sites in West Africa. Other important slaving ports in Nigeria were Badagry, Lagos on the Benin Bight, and Bonny Island on the Biafra Bight.

Slave routes were created all over Nigeria, connecting the interior with the major coastal ports. The Edo’s Benin Empire in the south, the Oyo Empire in the southwest, and the Aro Confederacy in the southeast were among the more prominent slave-trading kingdoms that participated in the transatlantic slave trade. Between the 15th and 19th centuries, Benin was a powerful nation.

On the other hand, between the Niger River and Lake Chad, the Hausa Kingdoms were a group of nations founded by the Hausa people. The Bayajidda legend chronicles the adventures of the Baghdadi hero Bayajidda, which culminate in the killing of the serpent in the well of Daura and the marriage with the local queen, Magajiya Daurama. While the hero had a child with the queen, Bawo, and another with the queen’s maid-servant, Karbagari, the hero also had a child with the queen’s maid-servant, Karbagari.

It is worthy of note that during the pre-colonial period, there is direct contact with Europeans working in port cities like Bonny, as well as indirect contact through the acquisition of European commodities through trade and the manufacturing of products destined for port cities. Of course, this trade was added to the slave trading networks that had been in place since around 1500. The interior of Africa was partitioned into colonial territories of European countries as a consequence of a meeting of European powers in Berlin in 1884.

Nigeria During the Colonial Era

The English moved into the Igbo country, which lasted from 1889 to 1914. For administrative concerns, northern and southern Nigeria were merged into a single British colony in 1914.

The advent of colonization can be traced to when the missionaries, who were part of the British government’s unarmed forces, infiltrated the Nigerian psyche. However, because of a lack of modern knowledge, Nigerians embraced churches and western ways of life, speeding up British penetration of Nigeria’s hinterlands. Meanwhile, history has it that because the church was primarily responsible for the abolition of the slave trade, it helped matters by increasing its popularity among the natives. The churches’ activities were first restricted to Lagos and Ibadan. British officials and traders scourged the West African coast, supported by Portuguese Roman Catholic priests, to convert the people of the region, especially those in the Edo Kingdom.

While the CMS operated mostly among the Yorubas, the Catholics focused on the Igbos. However, one of the factors that contributed to Samuel Ajayi Crowther becoming the first Anglican Bishop of the Niger was this. Later in 1925, a new movement arose. Nigerian students studying abroad, particularly in the United Kingdom, formed the West African Students Union alongside students from across the West African sub-region.

This union was primarily concerned with opposing colonial rule, but they also expressed strong opposition to the amalgamation. They blamed the British government for being the reason for Nigeria’s backwardness, claiming that they neglected to recognize tribal and ethnic divisions and instead merged all of Nigeria’s ethnic groupings together. These early nationalists were more concerned with their own ethnic groupings than with Nigeria.

At the same time, British scientists were interested in learning more about the Niger River’s route and surrounding villages. For generations, the delta obscured the river’s mouth, and Nigerians preferred not to tell Europeans about the country’s secrets. Mungo Park, an intrepid Scottish surgeon and naturalist, was commissioned by the African Association in Great Britain in 1794 to hunt for the Niger’s headwaters and follow the river downstream.

In the same vein, Hugh Clapperton, a Scottish explorer, heard about the mouth of the Niger River and where it met the sea on a subsequent journey to the Sokoto Caliphate, but he died before proving it due to malaria, depression, and diarrhoea. Richard Lander, his servant, and John Lander, Lander’s brother, were the ones who proved that the Niger flowed into the sea.

A number of British merchants, as well as some people who had previously been involved in the slave trade but had now switched their wares, were drawn to the Niger River by the legitimate commerce in commodities. The major corporations that constructed depots in the delta cities and Lagos were as fiercely competitive as the delta towns themselves, and they frequently used force to compel potential suppliers to sign contracts and meet their demands.

The Southern and Northern Protectorates were both eventually managed by the Colonial Office at Whitehall after the British government took control of them in 1900. The men who worked in this office were mostly from the British upper middle class—university-educated males who were not aristocrats and had fathers who worked in well-respected professions. Reginald Antrobus, William Mercer, William Baillie-Hamilton, Sydney Olivier, and Charles Strachey were the first five heads of the Nigeria Department (1898–1914).

The Governor, who oversaw the administration of his colony and had emergency powers, was appointed by the Colonial Office. His policies could be vetoed or revised by the Colonial Office. Henry McCallum, William MacGregor, Walter Egerton, Ralph Moor, Percy Girouard, Hesketh Bell, and Frederick Lugard were the seven men that ruled Northern Nigeria, Southern Nigeria, and Lagos from 1914 to 1914. The majority of these people had served in the military. All of them were knighted.

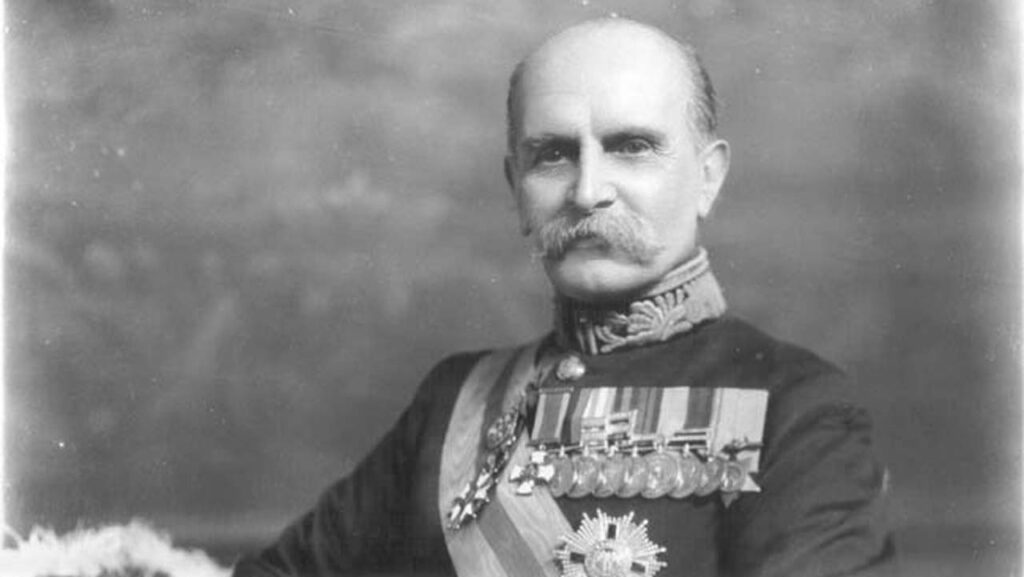

Frederick Lugard, who was appointed High Commissioner of the Northern Nigeria Protectorate in 1900 and served until 1906 in his first term, is frequently regarded as the British model colonial administrator. He had served in India, Egypt, and East Africa as an army commander, where he evicted Arab slave dealers from Nyasaland and established the British presence in Uganda. Lugard joined the Royal Niger Company in 1894 and was dispatched to Borgu to oppose French incursions. In 1897, he was tasked with forming the Royal West African Frontier Force from native levies to serve under British officers.

Sir Frederick Lugard (as he was known in 1901) spent his six years as High Commissioner developing the commercial sphere of influence inherited from the Royal Niger Company into a viable territorial unit under effective British political administration. His goal was to capture the entire territory and have the British protectorate recognized by the local rulers, particularly the Fulani emirs of the Sokoto Caliphate. When diplomatic efforts failed, Lugard’s campaign used armed forces to quell local resistance. Borno surrendered without a struggle, but Lugard’s RWAFF launched attacks on Kano and Sokoto in 1903. According to Lugard, unambiguous military successes were required since the vanquished people’s surrenders undercut resistance elsewhere.

Lugard’s success in northern Nigeria has been linked to his indirect rule approach, in which he ruled the protectorate via the monarchs who had been beaten by the British. The colonial power was willing to confirm the emirs in office if they accepted British authority, abandoned the slave trade, and worked with British authorities to modernize their governments. The emirs kept their caliphate titles, but they were accountable to British district officials, who held ultimate control. If required, the British High Commissioners might depose emirs and other officials.

Colonization remained the order of the day till 1960. There were a series of policies, events and projects initiated by the colonial masters ranging from the amalgamation of 1914, the Indirect rule system of 1916, the Developments in colonial policy under Clifford between 1919 to 1925, through the second world war from 1946 to 1950, to the introduction of self-government in some regions in 1957 to 1958.

These colonial activities gave rise to nationalist movements, which comprised influential Nigerian leaders who were confident enough to advocate for independence from the British rulers.

Nigeria’s Independence of 1960

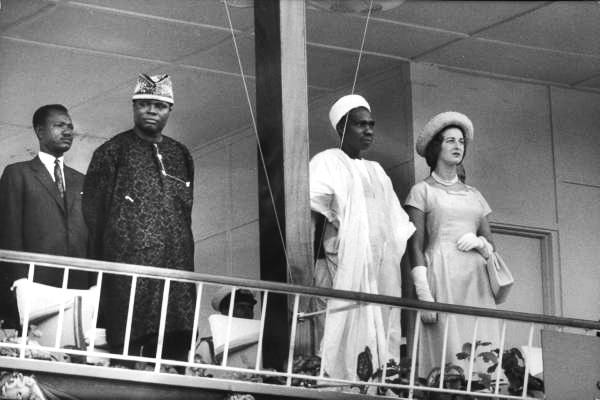

Nigeria gained independence on October 1, 1960, thanks to a British Act of Parliament. Jaja Wachuku was the first Nigerian Speaker of the Nigerian Parliament, often known as the “House of Representatives,” from 1959 to 1960. Sir Frederick Metcalfe of the United Kingdom was succeeded by Jaja Wachuku.

Jaja Wachuku received Nigeria’s Instrument of Independence, commonly known as the Freedom Charter, from Princess Alexandra of Kent, the Queen’s delegate at the Nigerian independence celebrations, on October 1, 1960, as First Speaker of the House. Nigeria’s monarch and head of state were Queen Elizabeth II, and the country was a member of the British Commonwealth of Nations.

Nigeria’s monarchy remained in power, but a bicameral parliament, a prime minister and cabinet, and a Federal Supreme Court exercised legislative, executive, and judicial authority. Political parties, on the other hand, tended to reflect the ethnic composition of the three major ethnic groupings.

The Nigerian People’s Congress (NPC) represented the Northern Region’s conservative, Muslim, predominantly Hausa and Fulani interests. Nigeria’s northern region accounts for three-quarters of the country’s land area and more than half of its people. As a result, the North has controlled the federation government since its inception.

The National Council of Nigerian Citizens, the second-largest party in the newly independent country, won 89 seats in the federal parliament (NCNC). The NCNC was formed to represent the interests of the Igbo and Christian-dominated peoples in Nigeria’s Eastern Region. The Action Group (AG) was a left-wing political group that supported Yoruba interests in the West. The AG won 73 seats in the 1959 elections.

Nnamdi Azikiwe was appointed Governor-General of the Federation, while Tafawa Balewa continued to lead a democratically elected parliamentary administration that was now entirely sovereign. The Governor-General was nominated by the Crown on the suggestion of Nigeria’s prime minister, in collaboration with the regional premiers, to represent the British monarch as head of state. When there was no parliamentary majority, the Governor-General was in charge of naming the prime minister and selecting a candidate from among competing leaders. Aside from that, the Governor-post General’s was largely ceremonial.

The administration was accountable to a Parliament made up of the 312-member House of Representatives, who were elected by the people, and the 44-member Senate, who were chosen by the provincial legislatures.

In general, both structurally and functionally, regional constitutions followed the federal model. The most notable exception occurred in the Northern Region, where special measures aligned the regional constitution with Islamic law and custom. However, the similarities between the federal and regional constitutions were deceiving, and the practice of public affairs showed significant regional disparities.

A vote was held in February 1961 to decide the fate of the Southern and Northern Cameroons, which were administered by Britain as United Nations Trust Territories. By an overwhelming majority, voters in Southern Cameroons chose to join historically French-administered Cameroon over unification with Nigeria as a separate federated entity. The mostly Muslim voters in Northern Cameroon, on the other hand, preferred to unite with Nigeria’s Northern Region.