The Ibibios are a group of people primarily found in the state of Cross River in southeast Nigeria. The average Ibibio village has about 500 residents. Each hamlet or village is made up of a group of rectangular complexes with many rooms that are placed around a courtyard.

The most significant ethnic group in Akwa Ibom State is known by the moniker “Ibibio,” which is widely accepted and used for both linguistic and ethnic classifications.

The lineage head, who may also be the secular leader, is a moral figure with ritual obligations who guards ancestor shrines. The traditions of descended from a single parent village or village group and the possession of a common tutelary spirit and totem bind groups of villages to form bigger geographical groupings.

It is worthy of note to state the striking similarities between the Ibibio people and the Anaang, Oron, and Efik peoples; they are said to be connected. This is because they share the same personal names, culture, and traditions as the Ibibio. In addition, the sub-clans including Anang, Efik, and Oron are thought to have originated as a result of the Ibibio’s early occupation of the region.

Meanwhile, history also has it that the Ibibio people’s current country of origin (Nigeria) is not where they originally came from. The information at hand points to Usak Edet (Isangele) in Cameroon as their native country.

In this piece, Naijabiography explores the history and culture of the Ibibio people, including their traditional beliefs, their political structure, and their trade and economic potential.

History

The Ibibio people, according to history, are thought to have been the region’s first occupants. They are thought to have arrived at their current location at approximately 7000 B.C. It is unclear when the Ibibio entered the state, notwithstanding the historical evidence revealing their dwelling in the state.

However, some researchers speculate that the Ibibios may have originated from the central Benue valley, namely from the Jukun influence in ancient Calabar. The extensive use of manila, a common form of currency used by the Jukuns, is another telling sign. Along with this, there is the Jukun drive to the shore in the south, which resembles how Akwa Ibom communities came to be where they are today.

The Ibibio migration story will be more succinctly explained by Cameroon, according to the most widely acknowledged account of Ibibio history. Oral testimony from field workers who claim that the core Ibibio people belonged to the Afaha lineage, whose ancestral home was Usak Edet in the Cameroons, supported this claim. The Ekoi people consist of the Usak Edet (Isanguele) as a subgroup (the Ejagham). This was based on the assumption that Usak Edet, a member of the Ibibio people, was known as Edet Afaha (Afaha’s Creek), reflecting the fact that Ibibio people descended from Usak Edet.

Following their initial arrival in what would later become Nigeria, the majority of the population first resided in Ibom. The Ibibio are thought to be the original inhabitants of the Ibom settlement, which was established by their Ibom ancestors and named Ibom in their honour. At Arochukwu, where they lived for a very long time and bowed down to the Sky God known as Abasi Ibom enyon.

Ibini Ukpabi was likewise revered by them (Ibritam). They abandoned the Ibom Kingdom and went to the modern-day Ibibioland due to conflicts with the Igbo people who were migrating south, which culminated in the Ibibio War that occurred between 1630 and 1720 A.D. In their current location near Ibom, a few villages have already been built.

The Ibibio people travelled south after the Aro-Igbo-Ibibio battle in 1550 A.D., where they discovered their current location, a virgin and unoccupied area. The Ibibio initially made their home at Ikono, from which point they migrated or dispersed to other locations, eventually becoming the indigenous people of the current Ibibio territories.

Ikono Ibom, a clan that was separated from the main Ikono Ibom, went to Ikot Oku Ikono village, which is presently in the Uyo Local Government Area at this point. Nsit Ibom relocated to Afia Nsit, now in Nsit Ibom, and Iman Ibom moved to Ekom Iman, now in Etinan Local Government Area. The three consider themselves to be Ibom offspring and blood brothers.

Ikot Oku Ikono, the main character in the Ikono Ibom Uyo clan, moved to Ikot Oku Ikono and formed the Ikono Anyaan and Ikot Ekpeyak Ikono. As stock and descendants of Ikono Ibom, the three offspring of Ibom have a common social, traditional, and cultural milieu.

The Ekom tree (coula edulis), which Iman Ibom, one of Ibom’s sons, planted there and gave the settlement its name. Ekom Iman is a native of the area where Iman Ibom settled. Iman had children, and some of them moved away to create new villages for the Iman Ibom clan, including Ikot Obioinyang and Afagha Effiate.

Ebre is the totem of the Ikono Ibom clan, who forbids the killing or maiming of this mythical animal. Upon the death of Iman Ibom, his spirit transforms into the Iman Ibom clan deity, “The Itina Iman deity,” and since oyot is the clan deity – totem, it is forbidden to kill or eat such mythical beasts. Water attracted Nsit Ibom to Afia Nsit, where he settled. His offspring then expanded to Mbak Nsit and other locations of that tribe. Iyak Anyan, the Anyan Nsit deity, is the totem of the Nsit Ibom tribe. They served as the focus of this study and had similar social, traditional, and cultural milieu traits in common.

The Ibibio People

In the 1963 census, the Ibibio were counted at over two million and were divided into the following six main regions: the Riverain (Efik), Northern (Enyong), Southern (Eket), Delta (Andoni-Ibeno), Western (Anang), and Eastern (Ibibio proper). These primary divisions are subdivided further into groups that can be distinguished by their geographic location. The Enyong (Aro), Calabar, Itu, and Eket groups of Efik are primarily found in the Calabar Province.

The Enyong (Aro), Calabar, Itu, and Eket groups of Efik are primarily found in the Calabar Province. The Kumba and Victoria ethnic groups live in the Cameroons, which are part of the Riverain region. The Enyong (Aro) and Ikot Ekpene of the province of Calabar, as well as the Bende division of the province of Owerri, are divisions of the Eyong. Within the province of Calabar is the Eket division.

The province of Calabar divides the Adoni-Ibeno into the Eket and Opopo. The two groups of Anang are the Abak and Ikot Ekpene of the province of Calabar, and the Aba of the province of Owerri. The Uyo, Itu, Eket, Ikot Ekpene, Enyong (Aro), Abak, Opopo, and Calabar groups comprise the Ibibio proper. They also comprise the Owerri Province’s Aba division.

The Economy of the Ibibio People

The Ibibio people engage in both subsistence and commercial activities. Just like the Efik, the Ibibio engage in trading fish and palm oil in considerable amounts, especially for commercial purposes, which helps to boost their economic growth.

Like their Igbo neighbours, the Ibibio are predominantly yam, taro, and cassava farmers in the rain forests. They work on subsistence farming. Plantains, chillies, maize, beans, and pumpkins are additional food crops. The majority of Ibibio’s wealth is derived from the export of goods containing palm oil, intra-tribal trade, and wage labour.

Similar to the Igbo, yams are traditionally seen as the main crop of men, while cocoyams are seen as the main crop of women. The majority of the yam clearing, planting, and harvesting is carried out by men. Women plant, weed, and care for other crops. The harvested yams are also gathered and placed in baskets before being transported to the market.

Ibibio people, particularly the Anang, are renowned for their proficiency in wood carving and are regarded as masters of this deft professional art. Women are typically in charge of producing mats, although young people of both sexes typically weave.

Political Structure

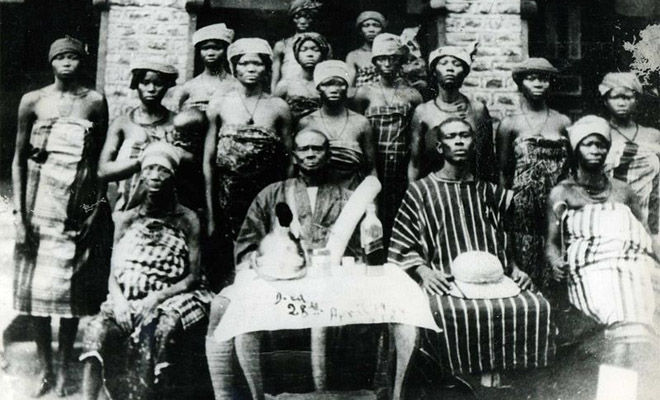

Ibibio society is traditionally composed of big blood-related families that live in communities each headed by an Ikpaisong, or constitutional and religious head. The Mbong Ekpuk (head of the families), along with the chiefs of the cults and organizations, make up the Afe, Asan, or Esop Ikpaisong (‘ancient council, shrine, or court’), under which the Obong Ikpaisong presided. Members of the Ekpo or Obon society, who serve as the spirits’ messengers, as well as the local military and police, enforced the decisions of the Obong Ikpaisong. If necessary, the chief will dispatch masked personnel to confront a rule-breaker.

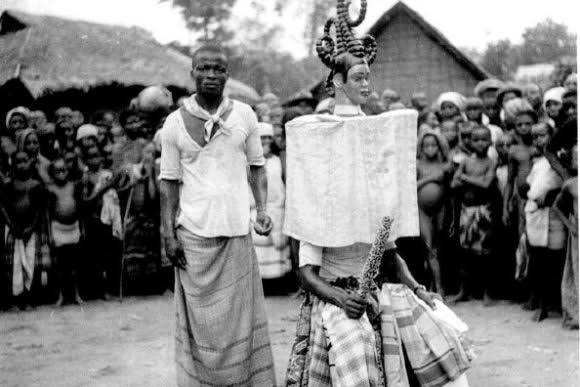

Members of Ekpo Masquerades wear masks at all times while carrying out their enforcement duties. Although the majority of people are aware of who they are, they rarely accuse the members who cross social lines and essentially engage in police brutality because they are afraid of reprisals from their ancestors.

All Ibibio males are welcome to join, but advancement into the politically powerful ranks requires access to wealth. Protecting its citizens and serving as a line of defence against possible assailants is Ekpo’s primary goal. They are focused on problems and crises that affect the town’s overall safety. Additionally, it gives men a way to channel their energy in a positive way for the good of all.

The Ekpo society is critical to the community’s existence from June to December. On days when the masks are out and being performed, many activities are forbidden, including farming, shopping, and getting food and water. Also at this time, crimes have harsher repercussions. Even though the penalties are less severe now, an individual found stealing in the 1940s during the Ekpo season would be slain by members of the Ekpo. Despite the fact that the community is well aware of its goals and operations, it is referred to as a secret society.

This is because during Ekpo season everyone is required to follow particular laws. The most crucial information is kept in a set of code words and dance moves that are taught to initiates and employed by members. Travelling during the season is made possible for members who are aware of these details; failing to do so will result in arrest if you are discovered.

The Obon society openly carries out its missions with a musical procession and popular involvement by its members, who include children, youth, adults, and brave elderly women. The Obon society is known for its strong, alluring traditional musical prowess and popular acceptability.

Religious History: the Present and the Past

Ibibio religion is known as Inam, and was divided into two dimensions and focused on the offering of libation, sacrifice, worship, consultation, communication, and invocation of the Supreme Being (Abasi Ibom), the God of Heaven (Abasi Enyong), and the God of the Earth (Abasi Isong) by the constitutional and religious head of a specific Ibibio community, known since ancient times as the Obong-Ikpaisong.

The worship of the Gods of the Heaven (Abasi Enyong) and the Gods of the Earth (Abasi Isong) through various invisible or spiritual entities (me Ndem) of the various Ibibio Divisions, such as Atakpo Ndem Uruan Inyang, Afia Anwan, Ekpo or Ekpe Onyong, Etefia Ikono, Awa Itam, etc., constituted the second dimension of The Temple Chief Priests/Priestesses of the various Ibibio Divisions served as the priests of these Deities (me Ndem).

A specific Ibibio Division could be made up of a number of connected autonomous communities or kingdoms that are headed by an independent Priest-King named Obong-Ikpaisong with assistance from the leaders of the several major families called Mbong Ekpuk, that make up the Community.

These have always been the Ibibio people’s traditional political and religious structure. Ikpaisong is the translation of tradition in Ibibio. In Ibibio Custom, a tradition called Ikpaisong represents the political and religious system. The word “Obong” in the Ibibio language is used according to the Office issue and denotes “Ruler, King, Lord, Chief, Head.”

The name “Obong” refers to the Obong-Ikpaisong and means “King.” The name refers to the Village Head and signifies “Chief.” The name signifies “Head” in reference to the Head of the Families (Obong Ekpuk). The term is a reference to God and signifies “Lord.” The name “Obong Obon” refers to the Head of many societies, such as “Head or Leader.”

Sacred areas, known as Akai, were dispersed across each town (forest). Because no one was allowed to clear them for cultivation, they were given the name “Akai.” All cemeteries, shrines to local deities, and gathering places for secret societies like Ekpo Onyoho, Ekpe, Ekoong, Idiong, and Obon were considered sacred. In these settings, everything was equally sacrosanct.

However, it was forbidden for non-members of the secret societies to visit the areas designated for them, not even to gather firewood, sticks, fruits (like mkpook), vegetables (like afang and odusa), snails, or to hunt the numerous forest animals.

The Ibibio term ukpong, which means “soul,” has four meanings. First, there is the ethereal body, followed by the soul, the spirit, and finally the over-soul; the latter always resides in the home of Abasi Ibom and is quite distinct from the individuality, which stays in the land of the dead in between incarnations. Even though the over-soul and spirit are combined, the incarnated part of the ego contains a significant amount of the Spirit.

Talbot claims that the Ukpong Ikot, or bush-soul, is the proper soul that sometimes manifests as a were-animal or a bush-beast in a forest or body of water. The shadow is believed to be an emanation of the soul and not to be tied to the ethereal body so that any action taken against it will directly influence the shadow.

The majority of Ibibio think that a person’s soul can be summoned into his shadow, which manifests as an image in a container of water. The shadow is subsequently speared, the man dies, and his blood can be seen in the basin’s water.

The Ibibio believe in obot, or that God created each person uniquely. If someone is wild, it is said that this is how he was formed; if he is kind, it is also said that this is how God designed him to be; if he is poor or rich, this is his lot; and so on. In other words, no one could change this person’s lot because he was created in this manner.

The Ibibio share the same beliefs in Essien emana, uwa, and fate. For instance, if someone died accidentally, he had to die that way because that is how he had died in his previous incarnation. If he was wealthy, he must still be wealthy today because he was wealthy in a past life; if he was intelligent, that is how he was intended to be; etc. However, he could change the course of events if he spoke with the Mbia Idiong, who was the only one who could advise him.

However, the diviners could assist him in determining what it was that he had done in a former life that was having an impact on this one. Then they may advise him on what to do to stop the situation from getting worse.

The work of early missionaries in the nineteenth century led to the conversion of the Ibibio to Christianity. Samuel Bill began working for Ibeno. He founded the Qua Iboe Church, which later extended over Nigeria’s central belt. Later, other churches such as The Apostolic church were also introduced. In the latter half of the 20th century, independent congregations like Deeper Life Bible Church began to establish themselves in the region. The majority of Ibibio people nowadays are Christians.

The first-ever Ibibio Bible translation was delivered at Ibom Hall in Uyo, the capital of Akwa Ibom, on August 27, 2020, making history. Published by the International Bible Society (Biblica), a 200-year-old American organization that also produces the NIV Version.

The Ibibio Bible was translated by Ibibio professors, including Drs. Paulinus Noah, Effiong Ekpenyong, and Rev. Fr. Dr. Donatus Udoette, a theologian who is fluent in Greek, as well as Professors Margaret Mary Okon, Bassey Okon, Eno-Abasi Urua, Inimbom Akpan, and Udo Etuk.

Ibibio Marriage

The four stages of the traditional Ibibio marriage are NDIDIONG UFOK, NKONG UDOK/NKONG USONG, UN MKPO, and USORO NDO (TM). The Ibibios’ marriage ritual begins with NDIDIONG UFOK, which literally translates as “to know the house.” The next stage of getting married is called “knocking on the door,” or “NKONG UDOK/NKONG USONG.” The formal declaration of intention is made at this point.

The male pays the woman a second visit to make a formal proposal and to collect the marriage registry. Literally, UN MKPO means “to give something.” On this day, the prospective groom presents the bride’s family with all the wedding-related materials. The Ibibio people regard it as a very important ceremony because it symbolizes the seriousness with which the prospective groom would treat his future wife.

The marriage’s distinctive trademark is USORO NDO (TM). A spectacular spread of food, including Edi kang ikong, Atama, Edi tan, Ekpan nku kwo, and music, opens the ceremonial presentation. It is stated that this is done to reassure the bride-to-be and the groom’s family that the wife will be a talented cook and won’t skimp on the food she prepares for her husband. The bride, who is exquisitely clothed in full traditional garb, dances wonderfully with maidens on her trail as the groom and his family enter the main location after finishing their meal.

Ibibio Food

The Ibibio people are renowned for being extremely wealthy in the food department. In fact, when it comes to native food, very few ethnic groups can compete with them. Afang soup, a crucial meal in Ibiobio culture that must be served for traditional marriages, edikang nkong (vegetable soup), and afere atama are prominent Ibiobio dishes (atama soup).