The Itsekiri ethnic group, also known as Jekri, Isekiri, or Ishekiri, lives in the westernmost portion of the Niger River delta in southern Nigeria. The Itsekiri make up a major section of Sapele, Warri, Burutu, and Forcados’ contemporary towns.

The Itsekiri are also a Yoruboid subgroup that primarily inhabits the Warri South, Uvwie, Warri North, and Warri South West local government districts of Delta State on Nigeria’s Atlantic coast. This implies that the Yoruba of South Western Nigeria and the Okpe and Edo peoples are relatives of the Itsekiris.

Furthermore, the significant Itsekiri communities can be found in many Nigerian towns, including Lagos, Sapele, Benin City, Port Harcourt, and Abuja, as well as in portions of the states of Edo and Ondo. Research also has it that the Itsekiris also like to refer to themselves as being a part of the Kingdom of Warri, also known as‘ in their language.

However, it is important to state that the main town, Warri, also known as the multi-ethnic metropolis, serves as the industrial and commercial hub of the Delta State region and is a significant location for the production of crude oil, natural gas, and petroleum in Nigeria. Thus, the vast mangrove swamps and freshwater wetlands where the Itsekiri reside are on the coast.

In this piece, Naijabiography explains the origin of the Itsekiris, their cultural heritage, including marriage, the way they dress, their religion, and socio-political tradition.

Origin of Itsekiri

The Itsekiri monarchy is still in place today, and Ogiame Olu Atuwatse III is the current head of state. The monarch’s main palace is located in Warri town, the area’s largest city and home to a variety of other communities, including the Urhobos, Ijaws, Isoko, and many other Nigerian and expatriate groups working in the oil and gas industry. Ode-Itsekiri, also known as “big warri” or “Ale iwerre,” is the historical capital of the Itsekiri people.

According to origin myths, Ginuwa, the first Olu (king) of Itsekiri, was once a prince of Benin, making all succeeding monarchs descend from the oba of Benin. The Olu used to receive advice from a council of lower chiefs.

However, the history of the Itsekiri people can be traced to the 15th century, when the Itsekiri had a hot-blooded and self-willed young man who was the Prince of Iginuwa, known to them as Ginuwa. Prince Iginuwa was the oldest child of Oba Olua, the fourteenth Oba of the Bini (Benin) kingdom. He was adored by his father, the monarch, but despised by the chiefs since he didn’t like adhering to the taboos and customs of the day.

Prince Iginuwa led gangs of fellow hot heads and started a frequent campaign of terror against the chiefs and their supporters because he was unwilling to wait for his time as an oba to come before doing away with what he thought to be wrong. As a result, the chief minister presided over a private gathering of the irritated chiefs who already harboured animosity toward him; the name of the chief was Iyase.

Later, history has it that a consensus was reached during the meeting with the chiefs for the young Prince to be eliminated. However, it is part of the custom that, especially in the Bini kingdom, the son who was chosen as the Edaiken, known to them as the crowned prince, is to live among the hereditary chiefs where his rank belonged.

Due to this, the young prince’s campaign could be carried out without the interference of his father, Oba Olua. Thus, the chiefs’ choice is also similar. However, Oba Olu sought advice from his top priest, named Ogiefa, about what should be done to spare his son’s life after learning the secret conclusion of what would probably happen to him.

Oba Olua’s consultation with the priest yielded a response from his oracle, in which the Oba agreed that there was a need to create an innovative way of smuggling the prince out of the kingdom as soon as possible.

Without further delay, Oba Olua gave the order to quickly build an “ark of iroko wood” that would be large enough to transport both the prince and the 70 eldest sons of the Bini chiefs. When the ark was finished, the central council was called together with the goal of doing this. Oba Olua notified the chiefs that he would be sending Prince Iginuwa to perform rites for the river goddess Olokun, and that he needed their first sons to go with him.

Since the Oba is the supreme head of the council, there was no objection to the order. So, effective immediately, an idea was created to evacuate the prince. Therefore, when the scheduled day arrived, nobody knew that Prince Iginuwa and his party—their sons—were leaving on a journey from which they would never return, with the exception of the Oba, the chief priest, and the palace attendant who devised the escape plot.

And in their ignorance, they joined the Oba in saying “OKHIENWERE O” to wish the prince safety and luck on his voyage. After that, slaves spent days dragging the ark through the thick woodland that crosses the current Sapele route.

Prince Iginuwa emerged from the iroko ark after it had been lowered to the river Ethiope’s banks, donned the royal robes, and started acting like a king. The hot-tempered Prince established himself as a monarch without a realm. However, after a protracted period of time, the Bini leaders came to the conclusion that their king had misled them, and they sent armies to retrieve Prince Iginuwa and their sons for the kingdom.

The prince would learn, in some way, that an assault was underway against him. He immediately ordered an evacuation after learning this and told everyone to board the ark.

And after leaving Ugharegin, where it is thought the Prince and his entourage had initially settled, they sailed to Efurokpe. However, the prince monarch did not feel secure in his new colony and headed out on another journey.

However, the trip would be lengthy, tiresome, and challenging this time. There was a certainty about how long it took the prince and his party to navigate the fierce waters of the Forcados River. And we are in no position to ask why, in turn. However, it so happened that their sailing brought them to the tiny town of Amatu, where they camped out for a considerable amount of time.

This, Amatu, is reputed to have been a beautiful and amazing location. Crocodiles and alligators slept on its gleaming white sand. The air was pleasant to breathe, and the sun’s rays were soothing to the skin. However, as these men were sojourners and not tourists, food was much more essential to them than the beauty of the natural world. Despite all its charms, Amatu was ineffective. However, the Ijohs also inhabited more fertile headlands (Ijaws). One of them was Oruselemo.

The accommodating nature of the Ijaws gave birth to a friendly relationship with the royal entourage. As a result, Oruselemo became more than just their home when Prince Iginuwa wed Derumo, an Ijoh woman.

In any case, a disagreement between the migrants and the Ijaws of Gulani (Ogulagha) developed over the woman, Derumo, after they had been in Oruselemo for a while. She had been murdered by the irate prince. And the warmth that had once prevailed between the Ijaws and the royal entourage was replaced by an icy coldness. Because of this, the wise prince king decided it would be better to move once more. The ark was sent into motion, and another journey was begun.

As the Ark turned north into the Warri River, they passed by the locations of Forcados and Burutu as they are today. It is stated that throughout the days of this specific quest, in addition to stress and suffering, sadness and gloom also saw fit to find solace in their souls.

After travelling for days, Prince Iginuwa and his party arrived in a virgin territory that would later become known as Ijala. At this point, Prince Ijijen (Ijiyem) and Prince Irame, two lovely boys, were born to him. Thus, they intended to build a little village there and settle.

However, soon after they began to feel at ease, word of their presence reached Bini, and as anticipated, an army was dispatched to recover the fugitive prince. It is noteworthy that the messages will always find a way to get through because this was a time when men were more spiritually inclined. They received the word at Ijala, and the mobile kingdom immediately began making plans for another evacuation.

But their commander’s soul has grown weary from the effort. Iginuwa was unable to leave Ijala. While things were getting ready, he joined his forebears. He was interred there as well. Due to this, Ijala has since 1500 AD been the only spot where Olus (Itsekiri monarchs) are interred. Also, there was no time for excessive grief because the danger was close at hand.

Primogeniture would make it easier for Prince Ijijen to assume the throne. And without raising a fuss, he was given the proper royal honours. Ijijen carried out the intended movement from Ijala with the aid of an Idibie (medicine man or diviner), who hurled a magical spear (Egan or Etsoro) that was thought to have landed in a spot known as Okotomu, now Ode-itsekiri (Big Warri).

With the aid of the Idibie, Prince Ijijen and his people were able to locate the spear after tracking its path. The Itsekiris are portrayed historically as a group of people with many ancestries. People who are multiracial, multiethnic, and complexly mixed.

Itsekiri People’s Tribes

Three tribes, the Ijaws, Sobos (Urhobos), and the Mahims, lived in the area that is now known as the Kingdom of Itsekiri or Iwere before the arrival of the Benin Prince Iginuwa.

However, because several communities in the Yoruba kingdom were involved in inter-communal fighting at the height of the struggle for kingdom carving, as a result, Ijebu-Ode, Akure, and Owo sent streams of migrants in. They managed to enter the kingdom, which at the time was not a kingdom, and made their way to a number of locations, including Ureji and Ugborodo.

This, however, should clarify the mysterious connection between the Itsekiri and Ijebu languages. There are also rumours that groups from the Igala region of the Nupe nation entered across the creek. This is because Fifan Wandobo and his brother Itsekiri travelled from Kerenmu to Ijalosan at the same time as other people during this exodus. Later, they would migrate from Ijalosan to Okoyitemi (Okolomu) under the direction of Itsekiri.

When Prince Ijijen’s lead ark landed, he was in charge of the settlement. At the sight of the iroko ark, a number of Itsekiri’s fellow countrymen fled, but Itsekiri and the other residents of the Okorotom quarter persisted. They lived with Prince Ijijen as his subjects and bowed to the authority of the aristocracy. This marked the start of a kingdom whose creation had been divinely planned by the invisible hand of fate.

The Culture of the Itsekiri People

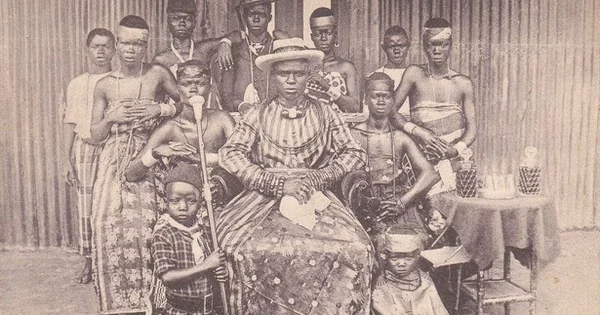

The Olu, the monarchy that oversaw traditional Itsekiri culture, and the council of chiefs, which make up the nobility or aristocracy, presided over it. The ‘Oloyes and Olareajas’, who were mostly descended from aristocratic houses like the Royal Houses and the Houses of Olgbotsere (Prime Minister or king creator) and Iyatsere, were the upper class of Itsekiri society, which was structured along the lines of a monarchy (defence minister).

Therefore, the Omajaja, or middle class, was made up of free-born Burghers, or Itsekiris. Due to the practice of slavery and the slave trade, a third class known as “Oton-Eru” or people descended from the slave class who had immigrated to Itsekiriland as indentured or slave labourers, was created. However, recently, the slave class is no longer present in Itsekiri society nowadays because everyone is regarded as a free-born.

Itsekiri men typically dress in a long-sleeved shirt called a Kemeje, a George wrapper tied around their waists, and a hat with a feather attached. The women fasten a George wrapper around their waist in addition to donning a blouse. They don colorful coral beads or nes (scarves) as headgear. The Itsekiris are renowned for their traditional fishing techniques, uplifting melodies, beautiful, fluid dances, vibrant masquerades, and boat races.

Itsekiri Language

Although it has been broadened to reflect their history as a trading tribe, the Itsekiri language is regarded as a Yoruba dialect. It now combines English, Portuguese, Bini, and Yoruba. This is because the Itsekiris are a complex mixture of the many different ethnicities and races that have settled in their area.

Due to similarities between the two languages (that is, Yoruba and Itsekiri) and the ease with which the sizable Itsekiri population living in Western Nigerian towns is able to pick up colloquial Yoruba terminology, modern standard Yoruba (the type spoken in Lagos) also appears to be impacting the Itsekiri language. Today, Itsekiri is taught in Nigerian local schools all the way through the university level.

The Itsekiri language, unlike nearly all important Nigerian languages, lacks dialects and is consistently spoken with little to no variation in pronunciation, with the exception of some Itsekiris who pronounce the letter “ch” instead of the regular letter “ts” (sh), as in Chekiri instead of the standard Shekiri. However, these are individual pronunciation traits rather than dialectal differences. This could be a holdover from earlier dialectal disparities.

Furthermore, there are some Itsekiri settlements that are semi-autonomous and whose history predates the founding of the Warri Kingdom in the 15th century, including Ugborodo, Koko, Omadino, and Obodo. The Ijebu, a significant Yoruba subethnic group, are claimed by the Ugborodo people as direct ancestors.

Religion

Like many other African cultures, the Itsekiris predated the arrival of Christianity in the 16th century by predominantly adhering to a traditional religion called Ebura-tsitse (based on ancestral worship), which has since become ingrained in contemporary traditional Itsekiri culture.

Other gods include Ogun, the god of iron and war, and Umale Okun, the god of the sea. Men proficient in contacting the Ifa oracle can perform divination, and rites are held for the ancestors on certain occasions.

Itsekiri Marriage

The marriage culture among the Itsekiri people, just like every other ethnic marriage, is believed to be a family affair, as it was done in the olden days. Marriages used to be arranged through the family in the past. The groom had never met with the bride before the wedding day. The bride is decked up in George and ornate coral beads, gold, and silver jewelry, while the men are clad in what is known as “Kimeje” clothing.

Itsekiri Foods and Dance

Itsekiri foods are majorly palm oil-made foods and seafood. Their foods include Banga Soup, Epuru, Usin/Owo Soup, Gbagba Ukpogiri, and Banga or Palm fruit or Eyes.

The Itsekiri people’s culture heavily emphasizes dance. Dances are typically only performed at significant life events. All around Itsekiriland, there are well-known national dances, yet any community could have its own local dances. Omoko, Ukewa, Ogono, and Jokotin are some of the most popular national dances.

Modern-Day Itsekiri

Despite being a small minority in Nigeria, the Itsekiri are thought to be a relatively wealthy and well-educated ethnic community with a very high percentage of literacy and a rich cultural past. The Itsekiri people, in particular, feel a sense of pride connected with receiving a western education because they have one of the longest histories of western education in West Africa. In the 1600s, an Itsekiri prince became one of the first Nigerians in the Warri Kingdom to pursue a western education.

The Olu of the Warri Kingdom, Olu Atuwatse I, Dom Domingo, a graduate of Coimbra University in Portugal in the 17th century, is one of the earliest university graduates among the Iteskiri people. Many Itsekiris can be found working in the professions today, particularly in the fields of medicine, law, and academia, as well as in business, trade, and industry. These individuals were among the forerunners who guided the development of the professions in Nigeria during the early to the mid-20th century.

A fusion of civilizations led to the development of the Itsekiris’ rich traditional and cultural legacy. Elders are chosen as leaders in the gerontocratic style of government used by the Itsekiri people. Priests are likewise held in high regard. They continue to consult the Ife oracle to communicate with their gods. They still hold on to the belief in “Oritse,” a universal God.