Once upon a time when women were trailblazers, advocating for equal opportunities through battles by the women’s forces. History has it that some women in the past are known for mobilising their fellow women in the markets, farms, and even in their compounds to request for their rights to be part of the decision-making processes of their society.

In the late ‘20s, some women rose to demand an opportunity to serve in public offices, not because they are power-thirsty, but because they felt the society had treated them as second-class citizens and had restricted their capabilities to just the kitchen and the other room.

Many years after, there have been campaigns on gender equality because from the ‘20s till now, the society still sees women as not capable of managing the affairs of the country or handling leadership positions- many even say women are the weaker vessels and are meant to be tendered by men.

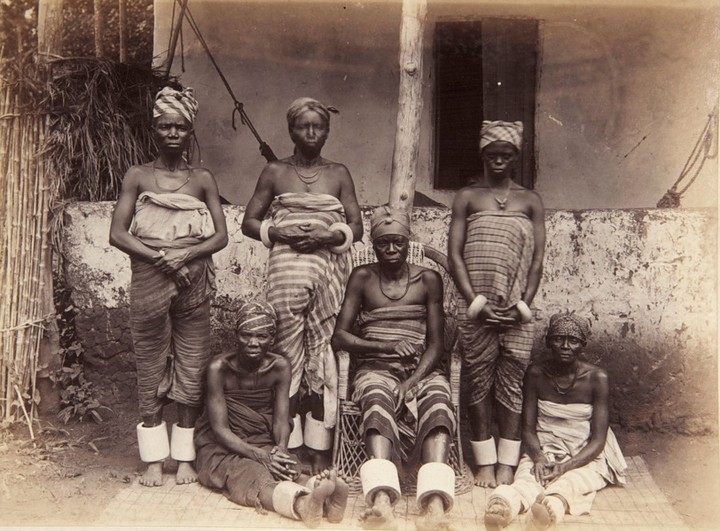

One such women-fold advocacy in history is that of the Aba Women Riot of 1929. In colonial Nigeria, there was agitation during the Aba Women’s Riot. Thousands of Igbo women from the Bende District, Umuahia, and other eastern Nigerian locations travelled to the town of Oloko to demonstrate against the Warrant Chiefs, whom they accused of restricting the role of women in the government. This however led to the outbreak of the protests, which involved women from six ethnic groups- Igbo, Ibibio, Andoni, Ogoni, Efik, and Ijaw, who participated in the protest.

The rural women of the provinces of Owerri and Calabar organized and took charge of the protest. The women participated in the protests by staging “sit-ins.” During the sit-ins, about 16 Native Courts were attacked, most of which were destroyed, and some Warrant Chiefs were forced to resign. History has it that It was the first significant female uprising in the whole of Africa, especially West Africa.

The protest resulted in the warrant chieftain system being eliminated by the colonial authority in 1930, and women were appointed to the Native Court system. Therefore, the African women built on these reforms, which are regarded as a precursor to the rise of widespread African nationalism.

History

The distribution of power in Igboland was considerably different from how it was in other parts of Nigeria. It was more difficult to impose Lord Lugard’s indirect rule system in Igboland since Igbos did not have a cohesive political institution like those in the North and South. However, Lugard devised a mechanism by creating the Warrant Chief, who oversaw the leadership and administrative activities of Igboland and they (warrant chiefs) were appointed as part of the indirect rule system.

These warrant chiefs, who weren’t always well-liked in their communities, rose to the position of enforced authority. And within a few years, the warrant chiefs grew more dictatorial due to their inherent power. The Native Revenue (Amendment) Ordinance was put into effect by the colonial government of Nigeria in April 1927. The lieutenant governor of Nigeria hired colonial resident W. E. Hunt to inform residents of the five provinces in the Eastern Region of the new ordinance’s contents and goals. This was done to provide the groundwork for the direct taxation that would be implemented in April 1928. Afterward, direct taxation on men was implemented in 1928 without any serious issues as a result of the meticulous propaganda in that year.

Later, Captain J. Cook, an assistant district officer, was dispatched in September 1929 to temporarily replace the district officer in charge of the Bende division. When he took over, Cook discovered that the nominal tax rolls were insufficient because they did not specify the number of spouses, kids, or cattle in each household. He then made the decision to add these to the revised nominal roll.

The riot started in a place called Oloko, when the warrant chief, Okugo, ordered his representative Mark Emereuwa to conduct the census for the tax on the morning of November 18, 1929. While Nwanyereuwa was processing palm fruit, Emereuwa entered her compound and gave her the order to count her stocks and persons living with her. Nwanyereuwa became enraged and responded by questioning him if his widowed mother was asked to pay tax. Meanwhile, she was fully aware that this implies you will be charged based on the number of the outcome.

In Igbo society, women were not expected to pay taxes. However, anger was shown through verbal scuffles that culminated in Nwanyereuwa dumping her palm oil on Emereuwa. Additionally, threats were traded during the pandemonium.

The widow went to the town square to talk to other women who were already debating the tax matter and shared her tragic experience with them. The women used palm leaves from other parts of the Bende district to spread the invitation after hearing Nwanyeruwa’s story.

A protest demanding the removal and trial of the warrant chief was conducted with the attendance of about ten thousand women. Two of the women were fatally injured when a British medical officer driving the same vehicle struck them by mistake as they arrived on Factory Road in Aba. The other ladies broke into the neighbouring Barclays Bank and the prison in a fit of rage in order to free their leader. They also demolished the local courthouse, manufacturers from Europe, and other buildings.

The Women’s War then extended to the Calabar province’s Ikot Ekpene and Abak divisions before turning violent and deadly at Utu-Etim-Ekpo, when on December 14 government buildings were set on fire and a factory was plundered, resulting in about eighteen women dying and nineteen being injured.

Although they did not seriously damage anyone during the riot, it is estimated that over 25,000 women were subjected to the cruelty that resulted in at least 50 women being slain. Additionally, Okugo, the warrant chief in charge of the Oloko area, received a prison sentence, and women were brought in to work in the courtroom.

History has it that the British administration abandoned plans to tax market women and limit the authority of warrant chiefs as a result of the Aba women’s revolt. Additionally, women were appointed to serve as a chief warrant in various districts, considerably enhancing their status in society.

Locally known as The Women’s War, the British dubbed it the “Aba’s Riot” in an effort to marginalise women’s contributions and alter the narrative.

About Oloko: The Origin of the Protest

The Aba Women’s War began as a result of an argument between Nwanyeruwa, a woman, and Mark Emereuwa, a man, who were both working on a census of the residents of Okugo, the town under the Warrant’s administration. Nwanyeruwa, who was of Ngwa descent, had wed in Oloko, a town. In Oloko, the census had to do with taxes, and the local women were concerned about who would tax them, particularly in the midst of the region’s hyperinflationary period in the late 1920s.

Therefore, the 1929 financial crisis made it difficult for women to sell and produce, so they asked the colonial government for assurances that they wouldn’t be obliged to pay taxes. The women agreed that they would forgo paying taxes and having their property valued if their political demands came to a halt. Since her husband Ojim had already passed away, Emereuwa went to Nwanyereuwa’s home on the morning of November 18. “Count your goats, sheep, and people,” he instructed the widow.

Nwanyereuwa became irate because she interpreted this to mean, “How many of these things do you have so we can tax you based on them.” Was your widowed mother counted? she retorted, implying that in traditional Igbo society, women are not required to pay taxes. Emeruwa grabbed Nwanyeruwa by the throat as the two exchanged furious remarks. Then from there, she went to the town to tell the other women what had transpired.

The Result of the Protest

The local colonial government was successfully contested and overthrown by the women thanks to their ability to adapt “traditional ways for networking and expressing displeasure” into potent mechanisms. The intensity of the women’s protests was something the colonial authorities had never seen in any region of Africa. All of the Owerri and Calabar Provinces, which are home to about two million people, were included in the six thousand square mile uprising.

Up to the end of December 1929, when colonial soldiers reestablished order, ten native courts were demolished, many others were damaged, the homes of native court employees were attacked, and European factories at Imo River, Aba, Mbawsi, and Amata were pillaged. Women broke into prisons and freed inmates. However, the colonial authorities’ response was equally crucial.

The last patrol in the Abak Division withdrew on January 9, 1930, and the last soldiers left Owerri on December 27, 1929. On January 10, 1930, the uprising was deemed to have been put down. More than 30 inquiries into collective punishment were conducted between late December 1929 and early January 1930. Since the new administration, led by Governor Donald Cameron, revised the Native Administration’s organisational structure, it is generally accepted that this event signalled the end of the women’s activities, according to Nina Mba. The Women’s War is thus considered to have had a significant historical impact on the British colonial administration in Nigeria.

The Women’s War gave women who weren’t married to the elites the chance to take part in social activities, which had a significant role in the development of gender ideology. The protests significantly changed the status of women in society. Women were able to take the role of the Warrant Chiefs in some locales. The Native Courts appointed women to serve on them as well. Many events in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s were inspired by the Women’s War, including the Tax Protests of 1938, the Oil Mill Protests of the 1940s in Owerri and Calabar Provinces, and the Tax Revolt in Aba and Onitsha in 1956. Women’s movements were particularly powerful in Ngwa land after the Women’s War.

Nwanyereuwa as a Trailblazer

Nwanyeruwa has been and continues to be the name that comes to mind when discussing the history of women’s militancy in Nigeria, and she has been connected to the development of African nationalism. The peaceful nature of the protests was largely due to Nwanyereuwa. Compared to many of the protest leaders, she was older. She advised the women to perform a song and dance protest, “sitting” on the Warrant Chiefs until they gave up their office’s insignia and resigned. As the uprising grew, additional groups adopted this strategy, resulting in the peaceful nature of the women’s protest.

Women from Oloko and other places brought money contributions to Madam Nwanyeruwa for her assistance in helping them avoid paying taxes. Other groups came to Nwanyeruwa to get in writing the inspirational results of the protests, which, in Nwanyeruwa’s opinion, were that “women will not pay tax till the world ends [and] Chiefs were not to exist anymore.” Unfortunately, a large number of women broke into Chiefs’ homes and attacked them, causing the uprising to be perceived as violent.