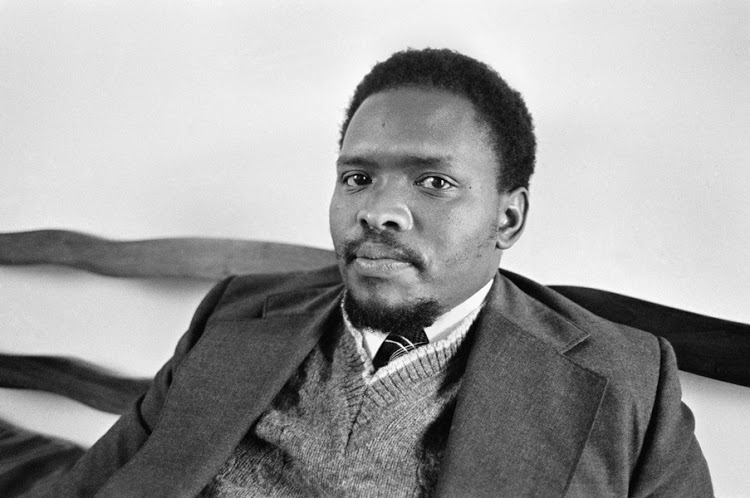

Bantu Stephen Biko, known as Steve Biko (who lived from December 18, 1946, to September 12, 1977), was a Bantu. He was a South African anti-apartheid campaigner and the leader of the Black Consciousness Movement, a grassroots anti-apartheid movement that took place in the late 1960s and early 1970s. He was an African nationalist and an African socialist in terms of ideology. Under the pen name Frank Talk, he wrote a number of quotes outlining his viewpoints.

Contents

Steve Biko Biography

| Full Name | Bantu Stephen Biko |

|---|---|

| Other Names | Bantu, Goofy |

| Date of Birth | 18 December 1946 |

| Place of Birth | Tarkastad, Eastern Cape South Africa |

| Died | 12 September 1977 |

| Place of Death | Pretoria, South Africa |

| Cause of death | Extensive brain injuries sustained from beatings by South-African security officers |

| Resting place | Garden of Remembrance, King Williams Town, Eastern Cape, South Africa |

| Occupation | Anti-apartheid activist |

| Organisations | South African Students’ OrganisationBlack People’s Convention |

| Spouse | Ntsiki Mashalaba (m. 1970) |

| Partner | Mamphela Ramphele |

| Children | 5, including Hlumelo |

| Net Worth | $1.5 million. |

Early Life and Education

Steve Biko was born on December 18, 1946, in Tarkastad, Eastern Cape, at his grandmother’s house but grew up and was raised in a Xhosa family, a poor one, in Ginsberg township in the Eastern Cape. His parents got married in Whittlesea. And he was the third child born to Mzingaye Mathew Biko and Alice “Mamcete” Biko. He had three siblings: Bukelwa, Khaya, and Nobandile. His parents got married in Whittlesea.

As a child, Biko was given the nickname “Bantu,” which means “people” in IsiXhosa; which he interpreted as “Umntu ngumntu ngabantu” (“a person is a person by means of other people”), “Goofy,” and “Xwaku-Xwaku,” the latter of which was a reference to his scruffy appearance. He was raised in his family’s Anglican Christian faith. In 1950, when Biko was four years old, his father became ill, was admitted to St. Matthew’s Hospital, Keiskammahoek, and passed away.

Biko attended St. Andrews Primary School for two years and Charles Morgan Higher Primary School for four years, both in Ginsberg. He was considered to be an exceptionally intelligent student, and for this, he was given permission to skip a year. In 1963, he transferred to the Forbes Grant Secondary School township. Biko was the top student in his class and excelled in math and English. In 1964, the Ginsberg community offered him a scholarship to attend Lovedale, a prestigious boarding school, alongside his brother Khaya.

Biko attended St. Francis College, a Catholic boarding school in Mariannhill, Natal, from 1964 to 1965. The school had a liberal political culture, which is where he first developed his political consciousness. He became especially interested in the replacement of South Africa’s white minority government with a government that represented the country’s black majority. Among the anti-colonialist figures who became Biko’s icons at the time was Algeria’s Ahmaad Boumediene. Biko praised the PAC’s “terribly good organisation” and the bravery of many of its members, but he was disappointed by its discriminatory racial policies. Nevertheless, he was not persuaded by its racially exclusive strategy and insisted that people of all races should band together to overthrow the government. In December 1964, he traveled to Zwelitsha for the ulwaluko circumcision ceremony, which served as a symbolic transition from boyhood to manhood.

Many people surrounding Biko discouraged him from pursuing his initial interest in studying law at the university because they thought it was too closely related to political activities. In 1966, he received a scholarship and enrolled in the University of Natal Medical School. There, he joined what his historian, Xolela Mangcu, called “a peculiarly sophisticated and cosmopolitan group of students” from all over South Africa. Many of them went on to hold important positions in the post-Apartheid era. As evidenced by the 1968 uprisings, the late 1960s saw a global heyday of radical student politics, and Biko was ready to participate in it. Shortly after enrolling at the institution, he was elected to the Students’ Representative Council (SRC).

Career

Biko again joined the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), a group strongly opposed to the Apartheid system of racial segregation and white-minority rule in South Africa. But later on, Biko discovered that the group was dominated by whites and got furious that white liberals, not the black people who were most affected by apartheid, dominated NUSAS and other anti-apartheid groups. Biko was a strong opponent of the apartheid system of racial segregation and white minority rule in South Africa. He thought that even well-meaning white liberals acted paternally and frequently lacked understanding of the black experience. His belief that black people needed to organise independently in order to resist white dominance, which began in 1968, led him to play a key role in the founding of the South African Students’ Organisation (SASO). Only “blacks,” a word Biko coined to refer to those who spoke Bantu as well as coloreds and Indians, were eligible for membership. He took care to keep his movement and ideas separate from white liberals, yet he had white friends and rejected anti-white prejudice. The government of the white-minority National Party first backed SASO because they saw it as a triumph for the racial separatist philosophy of apartheid.

Biko and his comrades formed Black Consciousness as SASO’s official doctrine after being influenced by the Martinican philosopher Frantz Fanon and the African-American Black Power Movement. The movement fought for the abolition of apartheid, the establishment of universal suffrage, and a socialist system of government in South Africa. It planned Black Community Programmes (BCPs) and put a special emphasis on black people’s psychological empowerment. Biko popularised the phrase “Black is Beautiful” to describe his belief that black people ought to shed any sense of racial inferiority. He helped establish the Black People’s Convention (BPC) in 1972 to spread Black Consciousness ideologies among the general public.

Biko’s activities were severely constrained in 1973, when the government issued a banning order after coming to view him as a potential subversive threat. He continued to be politically engaged, aiding with the establishment of BCPs in the Ginsberg neighbourhood, including a medical facility and a daycare centre. He received several anonymous threats while under suspension.

Biko was taken into custody four times and held for extended periods of time each time. He was detained at Port Elizabeth, South Africa’s southernmost city, in August 1977 after being taken into custody. Biko was discovered shackled and naked the following month, on September 11, in Pretoria, South Africa, some distance away. He passed away the following day, on September 12, 1977, from a brain hemorrhage that was later found to be caused by wounds he had received while being held by the police. South Africans were outraged and protested when they learned of Biko’s passing, and he soon gained recognition as a global anti-apartheid figure. Over 20,000 people witnessed his funeral.

Personal life

In 1970, Biko married Ntsiki Mashalaba. The couple had two sons, Nkosinathi and Samora. Later in 1977, he married Mamphela Ramphele, a prominent member of the Black Consciousness Movement. and had a daughter named Lerato, who was born in 1974 and passed away from pneumonia at two months old, and a son named Hlumelo, who was born in 1978. Also, Biko married his third wife, Lorraine Tabane. Both were blessed with a daughter, Motlats.

Biko’s prominence grew after his death. He was the subject of many songs and pieces of art, and the 1987 film Cry Freedom was based on a 1978 biography written by his friend Donald Woods. Throughout his life, Biko was accused of hating white people by the government, numerous anti-apartheid activists accused him of misogyny, and African racial nationalists criticized his coalition with colored and Indian people. Nevertheless, Biko rose to prominence as one of the first figures in the anti-apartheid struggle and is revered as the “Father of Black Consciousness” and a political martyr. His political legacy is still up for debate.

In addition, the English singer-songwriter Peter Gabriel released “Biko” in tribute to him, which was a hit single in 1980 and was banned in South Africa soon after. Along with other anti-apartheid music, the song helped to integrate anti-apartheid themes into Western popular culture. Biko’s life was also commemorated through theatre. The inquest into his death was dramatised as a play, The Biko Inquest, first performed in London in 1978; a 1984 performance was directed by Albert Finney and broadcast on television. Anti-apartheid cused Biko’s name and memory in their protests; in 1979, a mountaineer climbed the spire of Grace Cathedral in San Francisco to spread a banner with the names of Biko and imprisoned Black Panther Party leader Geronimo Pratt on it.

Ideology

Biko was influenced by his reading of authors like Frantz Fanon, Malcolm X, Léopold Sédar Senghor, James Cone, and Paulo Freire. The Martinique-born Fanon, in particular, has been cited as having had a profound influence on Biko’s ideas about liberation. Biko’s biographer, Xolela Mangcu, cautioned that Biko’s ideas were not solely developed by him but came from conversations with other black students who had been opposing white liberals for a long time.

Black Consciousness and Empowerment

Building on Fanon’s work, Biko rejected the apartheid government’s classification of South Africa’s population as “whites” and “non-whites,” which was indicated on signs and structures all over the nation. Biko saw “non-white” as a derogatory term that defined people in terms of an absence of whiteness. As a result, Biko substituted the term “non-white” with the term “black,” which he believed to be neither derogatory nor positive.

He described blackness as a “mental attitude” rather than a “matter of pigmentation,” referring to “blacks” as “those who are by law or tradition politically, economically, and socially discriminated against as a group in the South African society” and who identify “themselves as a unit in the Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement used the term “black” to refer to people who spoke Bantu, as well as Colored and Indian people, who together made up almost 90% of South Africa’s population in the 1970s. Biko was not a Marxist and believed that oppression based on race, rather than class, would be the main political motivation for change in South Africa. mostly because they want to separate us from any racial issues. In case they are affected negatively because of their race.

Foreign and domestic relations

In Biko’s opinion, the Bantustan system was “the greatest single fraud ever invented by white politicians,” as it was intended to divide the Bantu-speaking African population along tribal lines. He openly criticised the Zulu leader, Mangosuthu Buthelezi, claiming that the latter’s cooperation with the South African government was in violation of the Zulu people’s constitutional rights. He thought those opposing apartheid in South Africa should collaborate with those fighting anti-colonial movements elsewhere in the world and with activists battling racial prejudice and discrimination around the world. He also hoped that other nations would boycott South Africa’s economy.

In a post-apartheid society

Biko hoped that a socialist South Africa in the future would become a wholly non-racial society, with people from all ethnic backgrounds coexisting peacefully in a “joint culture” that incorporated the best aspects of all communities. He opposed minority rights protections because he thought that doing so would continue to acknowledge racial divisions. Instead, he supported a one-person, one-vote system. He initially argued that one-party states were appropriate for Africa, but, after speaking with Woods, he changed his mind about multi-party systems from one that initially supported one-party states for Africa. He thought that individual liberty was good but that food, employment, and social security were more important.

While conversing with Woods, about BCM, Biko insisted to Woods that “it isn’t a negative, hating thing. It’s a positive black self-confidence thing involving no hatred of anyone.” He acknowledged that a “fringe element” may still harbour “anti-white bitterness,” but added: “Frankly, it’s not one of our top priorities or one of our major concerns. Our main concern is the liberation of blacks.” In other places, Biko maintained that a vanguard movement must ensure that the black majority in a post-apartheid society would not seek retribution against the white minority. He said that this would necessitate educating the black populace on how to live in a non-racial society.

Legacy

Influence

Biko was referred to as the “Father of the Black Consciousness Movement” and the anti-apartheid movement’s first icon. While Nelson Mandela called him “the spark that lit a veld fire across South Africa,” justifying the Nationalist Government “had to kill him to prolong the life of apartheid,” Manning Marable and Peniel Joseph wrote in the introduction to an anthology of his writing in 2008 that Biko’s death had “created a vivid symbol of black resistance” to apartheid that “continues to inspire new black activists” over a decade after the transition to majority rule.” A professor of Communication Studies, Johann de Wet, described Bino as “one of South Africa’s most gifted political strategists and communicators.”

Quotes

Biko has written different quotes on various subjects.

- “Black man, you are on your own.”

- “The greatest weapon in the hand of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

- “It is better to die for an idea that will live than to live for an idea that will die.”

- “The most potent weapon of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.

- So as a prelude, whites must be made to realise that they are only human, not superior. Same with blacks.

- “They must be made to realise that they are also human, not inferior.”

- “Black consciousness is in essence the realisation by the black man of the need to rally together with his brothers around the cause of their oppression.”

- “At the time of his death, Biko had a wife and three children, for whom he left a letter that stated, in part: “I’ve devoted my life to seeing equality for blacks, and at the same time, I’ve denied the needs of my family.” Please understand that I take these actions, not out of selfishness or arrogance, but to preserve a South Africa worth living in for blacks and whites.”

- “I would like to remind the Black Ministry, and indeed all black people, that God is not in the habit of coming down from heaven to solve people’s problems on Earth.”

- “What black consciousness seeks to do is produce real black people who do not regard themselves as appendages to white society. We do not need to apologise for this because it is true that the white systems have produced throughout the world a number of people who are not aware that they too are people. “

Net Worth

Steve Biko’s net worth from his salary has accumulated to $1.5 million.

Social Media Handled

Biko did not have any social media handles.

on

on