People in the regions northeast and southwest of the confluence of the Niger and Benue rivers in central Nigeria are known as Igbira, also spelt Igbirra or Ebira. Their language belongs to the Benue-Congo branch of the Niger-Congo language family and is typically categorized as a Nupoid variant.

The Ebira are a central Nigerian ethnic and linguistic group. The Kogi, Nasarawa, and the Edo States are home to the majority of Ebira people. Before Kogi State and Kwara State split apart, Okene—which is close to the confluence of the Niger and Benue rivers—was considered the administrative hub of the Ebira-speaking population in Kogi State.

The Ebira Ta’o people have been located in four local governments since the creation of the state: Adavi, Ajaokuta, Okehi, and Okene, each with its own administrative centre. In the Federal Capital Territory, Ebira Koto may be located in Kogi and KotonKarfe local government areas, including Bassa LGA, Lokoja in Kogi and Abaji LGAs, and Nasarawa in Toto LGA. The Ajaokuta LGA is also home to the Eganyi. And the Etuno can be found in the Edo state town of Igarra in the Akoko-Edo LGA.

A dense, deciduous forest near the Niger and Benue rivers and a hilly savanna region away from the rivers are the two main ecosystems in the Igbira region. However, in the present-day Kogi State in the North-Central geopolitical zone of Nigeria, the Ebira can be found.

In this piece, Naijabiography explores the history and culture of the Ebira people, including their trade and economic growth as well as their social and political structures.

History

The Ebira people found themselves at odds with Fulani warlords to the north and west as the troops of the religious and political leader Uthman Dan Fodio conquered Hausaland. They were known as Igu (Koton Large) by Hausa, which means powerful land since they tried to conquer them but were never successful and were not conquered in the mid-nineteenth century.

Under the command of a warlord named Achigidi Okino, they engaged in combat between 1865 and 1880 with jihadists from Bida and Ilorin, known as the Ajinomoh. However, the Ebiras resisted the Fulanis’ conquest thanks in part to their environment’s inherent defences—their mountainous terrain.

The British government became interested in Ebiraland after the Royal Niger Company established a presence in Lokoja. The British established a military outpost in Kabba, west of Ebiraland, and the Ebiras soon became a target for annexation after they conquered Ilorin and Nupeland in 1898 under the guise of regulating the free movement of trade. The Ebira region came under British rule in 1903, despite fierce opposition.

A central authority designated by the British to represent Ebiras was in charge of overseeing several autonomous communities. The earliest of these leaders was Ouda Adidi of Eika, who ruled until 1903. Omadivi, a favourite of the British, replaced him. Moreover, the clan leader, Omadivi, had previously fought against Jihadists but favoured business with the British. He had little control over the other clans while he was in power. Adano was installed after Omadivi’s passing, however, his reign was brief. A new monarch, Ibrahim, was appointed in 1917.

Ibrahim was also known as Attah Ibrahim or Attah of Ebiraland and was an Omadivi maternal grandchild. Indirect rule was instituted by the British colonists during his administration, which was a key political move that boosted Attah’s power. Ibrahim united the autonomous villages under his political leadership by using his position as the head of the Ebira Native Authority, a procedure that some residents of those communities opposed.

He won the British government’s trust, and they gave him control over areas to the north of Ebiraland, like Lokoja. Ibrahim, who converted to Islam, assisted in the propagation of Islam in the area. Ibrahim, however, was banished in 1954 as a result of political machinations. His palace housed the neighbourhood’s first elementary school, where many of his kids received an education, and some went on to assume influential positions in the local and national administrations. Sani Omolori, who held the position of Ohinoyi of Ebiraland, succeeded Ibrahim.

The majority of accounts, however, link the migration to the Jukuns of the Kwararafa state, which is now in Taraba State and north of the Benue River. The Apete stool, which they brought with them from Kwararafa and preserved in a location in Opete (which gets its name from the stool), in modern-day Ajaokuta, is one of their remnants.

However, it served as their symbol of authority and group identity inside the kingdom. The current title instrument of Ozumi of Okene is the Apete. They first resided alongside the Igalas after migrating from Kwararafa, and the two groups coexisted for almost 300 years. The Ebiras moved to their ancestral house, known as Ebira Opete, in the region of Ajaokuta after the two clans split up after a disagreement.

Later, more tribes made their way south, discovering Okengwe, Uboro, and Okehi. These Ebiras settlements were independent societies without a central ruler or established royal dynasties in the past. Instead, they were led by the elderly in a form of gerontocracy.

Trades of the Ebira People

The majority of Igbira have historically worked in agriculture; they primarily farm yams, but they also grow beans, millet, and corn (maize). The rivers are used for both transportation and fishing. The majority of traders are women, who market both their own and their spouses’ produce.

Some groups in the nineteenth century raised and exchanged beni seeds. Additionally, the Ebira also place value on crafts and weaving as a major source of earning, for the development of their community. Although farming is still the primary occupation, modern Ebira social life has changed over the years.

People and Culture of Ebira

The Ebira culture is one of the oldest cultural systems that place more importance on its social formation or structure. That is, the Ebira people place more value on their people in terms of sustaining family formation to ensure that each family contributes to the development of the community at large.

The father, or the oldest man in the household, served as the family’s breadwinner, religious leader, and protector in the early history of the Ebira people (Ireh). Compounds (Ohuoje), made up of related or kin patrilineal families, Ovovu, the outer compounds, and lineages (Abara), made up of several connected compounds, are further significant social structures.

The Otaru is in charge of the Clan (Iresu), a group of related lineages in Ebiraland. Animal symbols, primarily the leopard, crocodile, python, or buffalo, are used to identify clans. A group of male elders representing various related lineages managed the affairs of the village.

Many Ebiras now live in urban areas and are influenced by Western and modern Nigerian culture. Polygamy and close ties to a related lineage are becoming less common, and the Attah or Ohinoyi is no longer the dominant political figure in the country. The awarding of chieftaincy titles to individuals, as is typical in many other Nigerian cultures, was another new custom that the Ohinoyi adopted.

The Religion of the Ebira People

Before the advent of colonization, when Islamic and Christian religions were introduced, the Ebiras had their own traditional beliefs and the gods that they worshipped. However, some Ebiras still practice their traditional religion, but a larger number of them have imbibed the western religion.

The Ebira people practised a type of African traditional religion before the arrival of Islam, with a primary emphasis on a god known as Ohomorihi, the rain-maker who resides in the sky. Rituals are carried out to satisfy a god who is said to punish evildoers and reward good ones. Furthermore, other prominent traditional gods of the Ebiras include the “Ohomorihi are ori” (deities) and spirits, which are other religious characters. The Ebira tradition holds that deceased ancestors reside in a spirit world.

Ebira Festival(s)

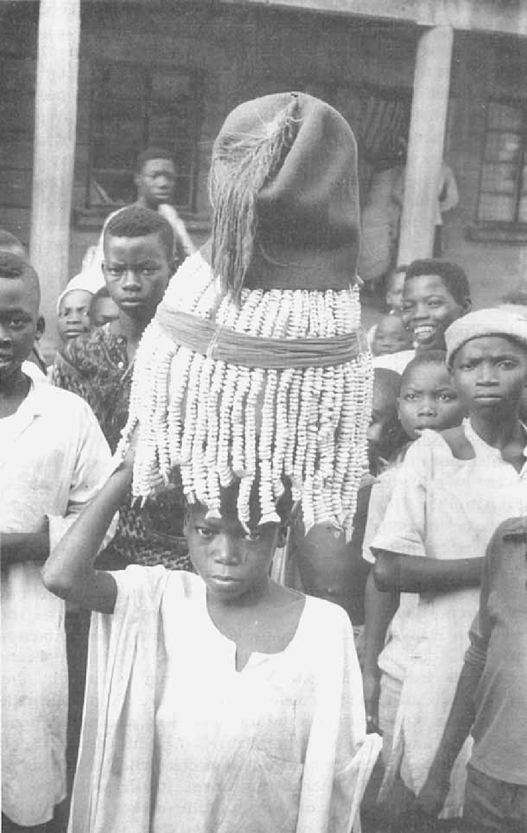

The Ekuechi festival, which takes place every year from late November through the end of December or early January, is the most well-known traditional celebration in Ebira villages. Because separate clans select their own dates to mark the celebration, it lasts a long time. In Ebira, “Eku” stands for an ancestor’s disguise, while “Chi” denotes descent.

Traditional Ebira culture holds that there is a land for the living and land for the dead, and individuals from the land of the living revere the land of the dead. Thus, ekuechi might be understood as the ancestors’ spirits coming back to the planet. The festival’s masqueraders are said to have access to the afterlife, where departed loved ones watch over the actions of the living.

These masqueraders convey encouragement and warnings from the spirit realm throughout the celebration. The event also heralds the conclusion of one year and the start of another. Eku’rahu’s masked performance, which focuses on singing, drumming, and chanting, is one of the festival’s main spectacles.