The Ibo, also known as the Igbo, are people who live in southeastern Nigeria and have a variety of intriguing customs and traditions. They are one of Nigeria’s largest and most powerful tribes, with a population of over 40 million people. The Igbos are well-known in Nigeria and around the world for their entrepreneurial endeavors and their passion to sustain their work-life history, which in different ways have been promoting the country’s economy.

In this piece, Naijabiography examines the origin, culture, and lifestyle of the Igbo people.

History

The Igbo people are derived from Eri, a heavenly person who was sent from heaven to start civilization, according to Igbo tradition. According to another legend, Eri was one of Gad’s sons who traveled down to build modern-day Igboland, as described in the Bible’s book of Genesis.

Igbos live in a region of Nigeria known as Igboland, which is divided into two regions along the lower Niger River. They are found in Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, and Imo states, as well as minor sections of Delta, Rivers, and Benue states. Igbo populations can also be found in Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea in small numbers.

Igbo people had their origin from when in Egypt, Eri was the determinant of who would be the next Pharaoh, which is law bidding. In those days, they had a god called ‘Emem’ who was in the custody of Eri as the religious adviser saddled with the responsibility of advising the Pharaoh of Egypt. During this period, Eri needed someone to assist him, so he enlisted the support of devotees. He had appointed all of these fanatics, but he needed to do something to truly establish their commitment. Meanwhile, they came to another confluence on their way to the southern side. The Ezu na Omambala tributary of the Niger and Benue rivers meets at this point.

The Kingdom of Igbo People

Agulu, Eri’s last son, stayed beside the sea since he was a fisherman. Eri, the first child, stayed at home with his father until he had a vision and was called to serve God in his own manner. Eri’s grandfather, Nri, was an incarnation of him.

As a result, Nri was Eri’s reincarnation, and the functions that their grandfather fulfilled were returned to him. He stayed at his father’s compound while his siblings went to their respective farming jobs. Ofo Ndigbo lives in Nri because the process is from one Eze-Nri to another. There is a handover known as Ofo and Alo, and you cannot become Eze-Nri without the original Ofo and Alo. For the past 1,009 years, the Ofo and Alo have existed.

Around 180 villages today may trace their roots back to Nri, and the civilization of Nri has spread throughout the world. He, like his father, formed the Ozo title and spoke about anything that had to do with fairness and justice. His grandfather’s name was Igbo, and he started everything on his grandfather’s behalf.

Aguleri, Eri’s last child, lingered at the side of the water’s edge. Aguleri is unable to claim that Nri is a descendant of Aguleri. Nri came from a place called Eriaka, which is currently defunct due to the departure of the principal.

Meanwhile, Eze Nri does not go to Aguleri to be crowned or purified, but as part of the custom, Eze Nri must proceed to where there is water divided into two after being crowned and other things perfected. History has it that they didn’t have any other water divided in two like the one found in Lokoja, the confluence of the Niger and Benue rivers. To them, the place is too far away, and the closest one is the Ezu and Omambala tributaries of the Niger and Benue rivers. According to research, they have two rivers there, and the covenant must be taken at one of them. This covenant is referred to as Udu-Eze.

Igbo Tradition

The centralized chiefdoms of Nri, Aro Confederacy, Agbor, and Onitsha divided the Igbo politically before British colonial authority in the twentieth century. The Eze system of “warrant chiefs” was introduced by Frederick Lugard. They were unaffected by the Fulani War and the subsequent growth of Islam in Nigeria in the 19th century, and as a result of colonization, they became largely Christian. The Igbo developed a strong sense of ethnic identity following decolonization. The Igbo areas seceded as the short-lived Republic of Biafra during the Nigerian Civil War of 1967–1970. Two sectarian organizations, the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra and the Indigenous People of Biafra, have been fighting for an independent Igbo state since 1999.

The Kingdom of Nri was a religious-political entity, akin to a theocracy, that arose in the Igbo region’s central core. Human (such as the birth of twins), animal (such as the killing or eating of pythons), object, temporal, behavioral, speech, and place taboos were among the Nri’s seven sorts of taboos. The taboos’ regulations were employed to educate and regulate the subjects of Nri. This meant that, while some Igbo may have lived under different forms of formal administration, all members of the Igbo religion had to observe the faith’s rules and obey the Eze Nri, the faith’s earthly leader.

Traditional Igbo political organization was founded on a republican system of government that was a hybrid of democracy and republicanism. This system, as opposed to a feudalist one with a king ruling over subjects, ensures equality for its residents in close-knit communities. The Portuguese, who first arrived and encountered the Igbo people in the 15th century, witnessed this governing system. Igbo villages and area governments were primarily ruled by a republican consultative assembly of the common people, with the exception of a few important Igbo towns such as Onitsha, which had Obi monarchs, and locations like the Nri Kingdom and Arochukwu, who had priest kings. A council of elders governed and administered most communities.

Igbo People and the Nigeria Civil War

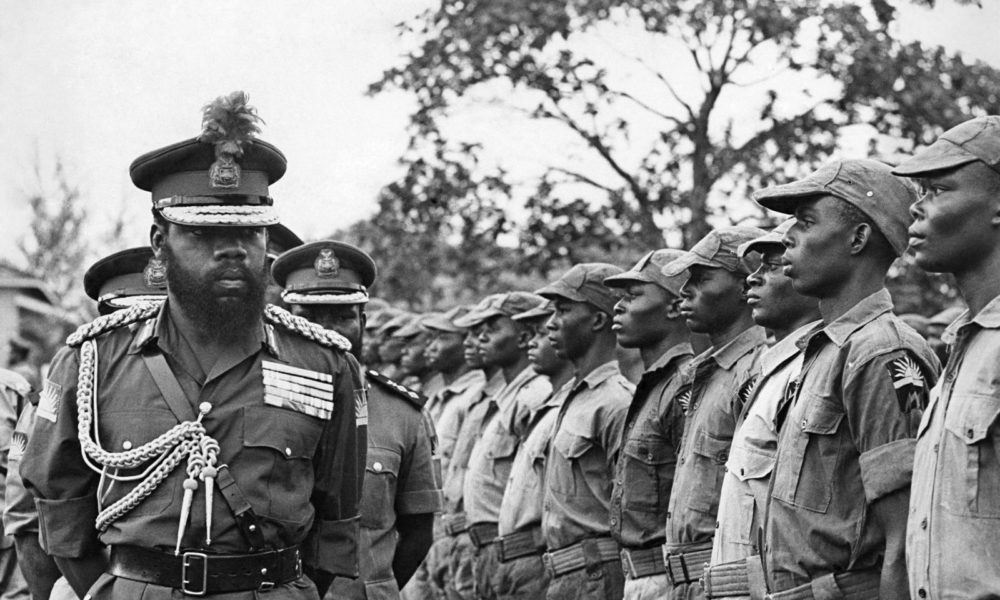

Between 1966 and 1967, a series of ethnic confrontations occurred in Northern Nigeria between Northern Muslims and Igbo and other ethnic groups from the Eastern Nigeria Region. The Nigerian military chief of state, General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi, was assassinated by army elements on July 29, 1966, and peace talks between the military government that deposed Ironsi and the regional government of Eastern Nigeria at the Aburi Talks in Ghana in 1967 failed. Following these events, a regional council of the peoples of Eastern Nigeria decided on May 30, 1967, that the region should separate and declare the Republic of Biafra. General Emeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu made the statement and was named the new republic’s first president.

The Nigerian Civil War, often known as the Nigerian-Biafran War, lasted from July 6, 1967, to January 15, 1970, after which the federal government re-absorbed Biafra into Nigeria. Several million Eastern Nigerians died as a result of pogroms against them, including as the anti-Igbo pogrom of 1966, which murdered between 10,000 and 30,000 Igbos. During the fighting, many homes, schools, and hospitals were destroyed. Nigeria’s federal government denied Igbo people access to their savings, which were held in Nigerian banks and offered them minimal compensation. The battle also resulted in widespread discrimination against the Igbo people by other ethnic groups.

Biafrans earned the esteem of personalities such as Jean-Paul Sartre and John Lennon, who returned his MBE partly in protest of British support for the Nigerian government during the Biafran War. Odumegwu-Ojukwu claimed that his people had become the most cultured and technologically proficient black people in the world during their three years of freedom. Odumegwu-Ojukwu resumed his proposal for the Biafran state to secede as a sovereign nation in July 2007.

Following the battle, some Igbo subgroups, such as the Ikwerre, began to separate themselves from the main Igbo community. Persons in eastern Nigeria altered the names of people and places to non-Igbo-sounding words after the conflict. The town of Igbo-uzo, for example, was anglicized to Ibusa. Many Igbo struggled to find work as a result of prejudice, and the Igbo became one of Nigeria’s poorest ethnic groups in the early 1970s.

The Igbo rebuilt their cities on their own, with no help from Nigeria’s federal government. As a result, new factories were built in southern Nigeria. Many Igbo people eventually worked for the government, and many more ran their own businesses. Nigerian Igbos have been migrating to other African countries, Europe, and the Americas since the early twenty-first century.